One of the most important things to understand if you care to understand the world around you is colonialism. From the mid-1400s to now, certain nations, almost all European, have sought to spread their influence via turning other nations and regions into colonies. These colonies saw vast improvements to infrastructure, education and health, but at the price of independence, freedom of expression, freedom of movement and, in many cases, outright violence bordering on genocide. I have no illusions about giving you a complete overview of the various colonial empires that have spread across the globe since the middle of the fifteenth century, nor is my aim to take a moral stance on the practice (obviously it was terrible, I’m not going to beat you over the head with that fact like you don’t understand it). My goal instead is to give you a basic outline of when these empire’s started, their basic expansion and their eventual downfall. So, without further rambling, here is a concise guide to 8 colonial empires.

- Dutch Empire

I’m going to go in a rough chronological order (rough mind you) and in my mind this means starting with the Dutch. The Dutch Republic was a small but powerful European power that used its maritime skills and resources to spread their influence out from just their small and exposed European kingdom. The original Dutch colonies came about as trade efforts. Dutch traders set-off to the east where they got an early if short-lived monopoly of the spice trade started. These early Dutch traders set up coastal forts, trading posts and ‘factories’ in an effort to create an expansive commercial empire, i.e. their goal was to control resources and trade, not land or people.

By 1595 the Dutch had reached as far east as Java and in 1602 the Dutch East India Company was founded to oversee this new commercial opportunity. By 1621 the Dutch East Indies Company was deemed necessary and a rivalry with Portugal was developing. The Dutch tried to push the Portuguese out of the spice trade and began harassing their colonies in Brazil in the mid-1620s. In 1626 they set their sights on North America and bought the island of Manhattan from the natives, rechristening it New Amsterdam and trying to gain a foothold alongside the French, Spanish and Brits on the East Coast of North America. Dutch Guiana was added to the empire in 1630, they failed to take the Philippines in 1646 and then added Suriname to the empire in 1650. Once Suriname was in their possession, the Dutch started to destroy certain spice crops, relegating them to only a few islands under their control. In 1652 they found a colony at the Cape of Good Hope in Southern Africa and in 1658 they wrestled Sri Lanka from Portuguese control.

From here the empire begins to crumble, though it takes until the twentieth country for the entire enterprise to be undone. It starts with the British capturing New Amsterdam with very little resistance in 1664. Then in the late 1700’s they began to loose control of their colonists in South Africa, now calling themselves Afrikaners, and the early 1800’s they began losing control of the same area to the British, finally being expelled for good in 1815. This left the Dutch with a few possessions in South America and the ‘Indies’, but little else. After World War II Indonesia finally shook off Dutch control and even Suriname, their final major possession, eventually achieved independence in 1975.

The legacy of the Dutch was not as horrific as some, but certainly not a net positive (I’m not going to argue any of them are in case that statement worried you). The Dutch spread their language, culture and architecture to their colonies and many of these cultural remnants remain today. In addition the Dutch, more than some of the fellow colonizers, sent a good deal of the home population out to the colonies, an event some call the Dutch Diaspora. Hence you can find Dutch communities in various lands their forefathers once conquered or controlled. Perhaps their most lasting impact though was their system of using colonies as bases for cash crop production and trade. They certainly weren’t the only ones to do it, but they may have been the first, at least in this era.

2. Portuguese Empire

If the Dutch started the rush eastward to corner the spice trade and eastern trade routes, then the Portuguese started the rush to claim and conquer the ‘New World’. The Portuguese empire sprang out of the wars of reconquest, the hundreds of years it took Spain to take Iberia back from the Muslim invaders of the 700s. The end of this brutal conflict left a host of military men with no one to fight and nothing to do. Luckily for them, and unluckily for half of the globe, this period coincided with early Portuguese maritime exploration efforts. Their earliest colonies were in North Africa and West Africa and served as military bases and, in the case of the islands of Madeira and the Azores, sites to cultivate wheat. Again, much like the Dutch, these early colonies were intended to stimulate trade, not conquest. In the 1450s a Papal Bull from the Catholic Church gave them the green-light for more African conquests so they added the Cape Verde Islands in 1462, built a castle in modern day Ghana in 1482 and left a string of forts around the Cape of Good Hope in the 1480s. By the 1490s the Portuguese were seeing real economic gains from their many colonies, annoying European neighbors and forcing them to consider empires of their own.

The biggest event in early Portuguese colonial history came with the Papal Bull of 1494 that split the newly discovered Americas between Spain and Portugal exclusively. While Span would go on to conquer large swaths of North and Central America, Portugal’s focus became the land soon to be known as South America, more specifically, the area in and around modern day Brazil. Around this time the Portuguese also became the first Europeans to build forts and trading posts in India. In fact, until gold and silver were found in Brazil, the area was largely ignored in favor of getting a foothold in India, a land already known for its vast riches and resources. In the early 1500s the Portuguese seized the city of Goa, captured Malacca in Malaysia and began trying to force the Dutch out of the spice trade. In 1514 they took control of the Straight of Hormuz and in 1534 they captured Bombay. Brazil became a Royal Province under the control of a Governor in 1549 and slaves began being shipped to the new province a year later in hopes of turning it into a plantation colony or a mining hub. By 1557 they had added a colony off the coast of China to their empire and now had footholds all around the known world.

By the late 1500s and early 1600s though, the pressures of maintaining an empire started to take their toll on the Portuguese. In the 1580s they got wrapped up in an Angolan civil war. Between 1646 and 1658 the Dutch expelled the Portuguese from nearly all of their major Eastern colonies, in the 1660s the Spanish and British took the rest and by the late 1600s the Ottomans had done the same in Mombasa and Zanzibar. If there was any good news for the Portuguese during this period, it was the discovery of gold and silver in Brazil in 1698, leading not only to a rush to acquire the precious metals but an influx of slaves to pull them out of the ground. Brazil was now the focus of the Portuguese crown. The city of Sao Paulo was founded in 1711 and the Treaty of Brazil expanded the province’s borders in 1750. Then, in 1763, a tsunami hit Lisbon, killing 1/3 of its population and making a Brazil a far more important and substantial chunk of the Portuguese empire. In 1763 Rio became the capital and in 1775 the various ‘states’ of Portuguese South America are combined into one centralized ‘Brazil Colony’. The first major rebellion was quashed in the late 1780s, but was only a taste of what was to come in South and Central America in the 1800s. As the 1700s closed, the first census of the Brazil Colony was taken and it recorded a population of 3.25 million, 2 million of which were African slaves or of African descent.

The down-slide began in 1808 when the French Invasion of Portugal led the crown to put Brazil and the home-country on equal legal footing. This taste of not technically being under a European thumb seemed to go over well with the Brazilian leadership. In 1822 a man named Don Pedro declared himself King of Brazil and announced the colony’s transition into an independent kingdom. The Portuguese were now a shell of their former selves as far as their empire was concerned. They had held on to their African colonies, but the rest was gone with little hope of being recovered. In the latter half of the 1800s they did spend a lot of effort suppressing the slave trade, eventually making it illegal in the latter half of the 19th century. They lost the rest of their colonies (Angola, Mozambique & Goa) during the wave of independence movements of the 1960’s and 70’s. Their last major possession, Macau, was finally returned to China in 1999.

Like the Dutch, the Portuguese were some of Europe’s earliest colonizers. Also like the Dutch, this early start seemed to make them a target for the latter powers despite the fact that these same powers copied their entire system of colonization. Like their fellow colonizers the Portuguese spread their culture and language to their colonies. They also helped to bolster the slave trade early on, importing a significantly higher number of slaves than even the United States. Sure they worked to end the practice once they had no use for it any longer, but that isn’t as impressive as some historians seem inclined to make it out to be.

3. Spanish

The story of the Spanish mimics that of the Portuguese quite a bit for quite some time. Like their Iberian neighbors, the Spanish had a ton of soldiers with nothing to do post war of reconquest, they had an early maritime exploration culture and they received backing from the Church in the New World. Unlike the Portuguese, the Spanish seemed happy to go all in on the New World from the start. After word from Columbus and his contemporaries reached the Spanish monarchy, they got right to work colonizing. Their first colony was in Santo Domingo in 1496. They then claimed the entire pacific coast of North America in 1513 and conquered Cuba two years later. Cortes brought down the Aztecs in 1521 and by 1525 Conquistadors were beginning to settle in Central America. The conquest of Peru came soon after in 1533 and Columbia and Venezuela had been reached by 1543. Around this time the Spanish Monarchy and the Church, aware of how horribly the natives of this new land were being treated, tried to enact laws for their protection, but they were largely unenforceable and did little to alleviate the genocide taking place on the conquistadors’ watch. In 1545 silver was found in Bolivia and countless natives and slaves were sent to their deaths to extract the precious metals. In 1571 the Philippines were added to the Empire and constituted a good base of operations on the other side of the Pacific for the now global Spanish Empire. In 1605 they expelled all of the Muslims from any and all of their colonies.

Things began to go awry for the Spanish in the late 1600s/early 1700s. Haiti is ceded to France in 1697 and the Spanish Netherlands are lost in Europe in 1714. By 1776 the Spanish Empire in the Americas is split into four Vice Royalties and within fifty years, the rebellions begin. First to rebel is Bolivia in 1809 and the revolution soon spreads to the rest of their Latin American Empire. By 1823 they had lost everything but their possessions in the Caribbean and the Philippine Islands. The Caribbean colonies rebelled in 1868 and were lost. Spain then tried to pivot its focus to Africa, beginning to take control of Western Sahara in 1884, but war with the United States in 1898 proves to be the final nail in the Spanish Empire’s coffin. By the time the war ended, Spain had lost not only quite a bit of prestige, but all of its colonial possessions (Philippines went to the US and everything else was sold off). Spain was not through yet though. They controlled Morocco for the first half of the 20th century, though that ended in 1956, and lost control of Equatorial Guinea in 1968.

The Spanish empire was one of the world’s largest, earliest and most devastating. The Conquistadors and their descendants committed open genocide, enslaved millions, and pioneered the worst of the plantation and mining systems found in the pre-Abolition New World. They also saddled Latin America with a racial caste system that still effects people of certain skin tones or racial makeups to this day. Like the Dutch and Portuguese, they spread their language, culture and religion, but these hardly off balance the centuries of brutality and murder committed by the Spanish and in many cases were used to justify it.

4. French

France is unique to the colonization story in that it has two distinct eras of Empire. The first ranged from the mid-1500’s to 1803 and the second lasted from the 1830s to the modern day. Unlike the rest of our list so far, the French were not part of an early maritime culture, they were not gunning for a monopoly of the spice trade and had a rival who was also new to the game (the British). The goals of the French colonizers were numerous, but fairly set in stone; bring French culture to the natives, bring Catholicism to the heathens, dominate the fur trade in the north and set up a plantation economy in the south. The first imperial effort began in 1535-36 when Jacques Cartier, an explorer funded by the French, explores the Hudson Bay, makes early contact with the Iroquois and founds the future capital of Montreal. Things stall out for a bit after that, attempts to colonize Brazil and Florida are rebuffed by the Spanish and Portuguese, but begin to look up again in 1608 when de Champlain founds Quebec City. In 1630 they add a ‘Guiana’ colony to sit alongside the British and Spanish versions and in 1638 they construct a trading station on the Senegal River. In 1660 New France is named a Royal Colony and in 1668 the Jesuits there found Sault St. Marie, which opens the lands south of the Great Lakes to French exploration. A year later an explorer name De Salle explores the Ohio River Valley, an expedition France would claim entitled them to the territory (the Brits strongly disagreed). By 1690 they had added six forts in and around India and a confrontation with British began to seem inevitable.

The early 1700’s saw tensions between the French and British colonies reach their peak. By 1749 the French were pressing their claims in the Ohio River Valley and the Brits were sending envoys, one none other than a young George Washington himself, to convince them to leave the Valley to the Brits. The issue cannot be resolved by diplomats and emissaries so the two countries go to war in 1754. Known as the Seven Years War in Europe and the French & Indian War in North America, this military venture cost France everything. By the time the war ended in 1763, France had been forced to give all of her territory to the Brits and Spanish, leaving it with only Haiti and New Orleans in the New World. In 1800 greater-Louisiana was ceded back to the French, now under the leadership of Napoleon. While Napoleon originally intended to reestablish the lost French Empire in North America, he eventually decided to sell it to the US in 1803, the same year Haiti was lost to a revolution. These were nearly crippling blows to the French imperial effort, but as focus shifted to Africa, France was ready for a second try at Empire.

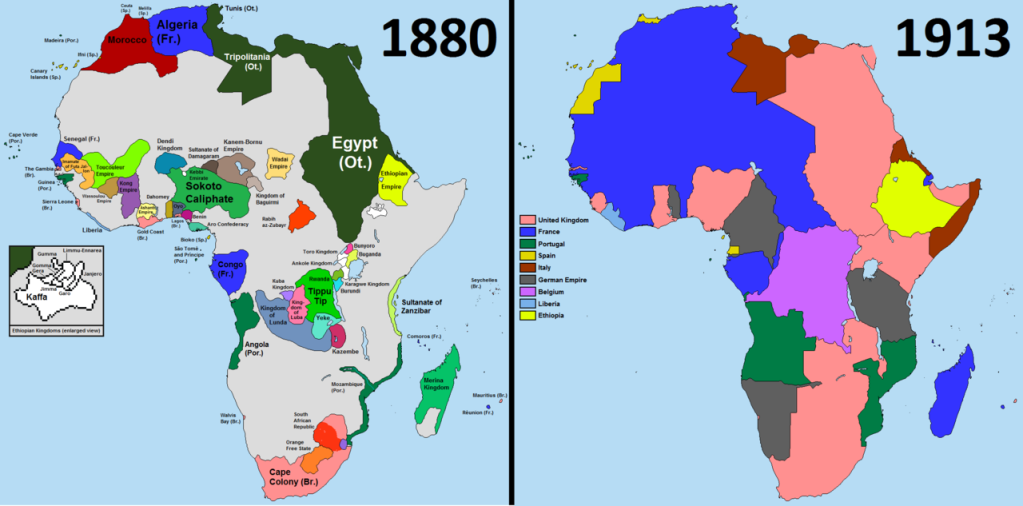

Things began in the 1830’s when tensions with the Ottoman Empire led the French to take control of Algiers. Within a decade a holy war, one of many, had been declared on the French, but they dug in and met violence with violence to keep their newest possession and last shot at a competitive empire. In 1858 they made what would one day be seen as their most colossal colonial blunder; they tried to colonize Vietnam. While things went well at first, for the French anyway, we all (should) know how that effort ultimately played out. In 1869 France was given joint control over a bankrupt Tunisia, giving them an even bigger foothold in North Africa. With the scramble for Africa kicking off in the 1880s, France did all it could to expand its African Empire before the other European powers descended on the continent. In 1881 they invaded Tunisia from Algeria and in 1883 they began the conquest of Madagascar. In 1887 they combined Cambodia and Vietnam into the colony of French Indochina and in 1889 they came to an agreement on the Senegal/Gambia border with Britain. The 1890s saw even more conquest, though increasingly in the form of ‘protectorates’, a fancy way for the Europeans to colonize without colonizing; Dahomey in 1892 and the Ivory Coast & Laos in 1893. In 1906 they gained informal control of Morocco alongside some other European powers and in 1910 established French Equatorial Africa.

Like the rest of the colonial powers, the two world wars of the 1900s meant an end for France’s pre-war empire. Admittedly the protectorate system of WWI put even more countries under France’s control (mainly Syria and Lebanon), but only for a short time. Perhaps the worst moments in French Imperial history came in the time after WWII. Having suffered greatly at the hands of the Germans, many French citizens saw the colonies as little mini-Frances they could run away to if trouble ever struck the motherland again. This came into play in the wars in Indo-China and Algeria. In both instances the French were ruthless in their attempt to retain power, but in neither case were they successful. After years of bloodshed and a drop in international prestige, the French finally gave up in both wars and allowed their colonies to choose their own futures (though the US put a damper on that attempt in Vietnam). While France had lost some of its smaller colonies during the wars in east Asia and north Africa, the majority of them were allowed independence without a struggle in the 60s and 70s. Cameroon, Togo, Mali, Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, Gabon, the CAR, Senegal, Mauritania and Djibouti were all born out of defunct French colonies in this era.

In the end, the French were not your typical colonizers, though that isn’t meant to be a compliment. Their early presence in North America, especially in Canada, is sometimes viewed as the ‘best type’ of colonialism. This image of the individualistic fur trader, living among the natives and learning their ways, stands in stark contrast the French plantation owners of Louisiana and the Caribbean who were as vicious as any Conquistador on his worst day. Like all colonizers, they brought their culture, architecture and religion along with them, though they did not settle in the numbers peoples like the Dutch did. Perhaps the most interesting part of French colonialism was its insistence on spreading the French education system. Many of the local elite were sent to Paris for schooling and more than a few returned home with radical ideas that led to the very revolutions that cost France her empire and international standing.

5. English

It was once said that the sun never set on the British Empire. This was meant to be a reflection on their might and reach, but was also somewhat accurate. At its height, the Empire controlled just shy of a quarter of the world’s population albeit through a system of indirect rule. In this system the British transplanted their own legal and administrative systems into a conquered land, but allowed locals to run these systems under British guidance (that’s an over simplification, but books have written on this subject and I’d prefer not to bore you to death). While this may seem preferable to direct rule, the methods of keeping control and the basic principles of exploration remained the same. Of all the empires on our list, this one is the one with the most intact possessions to this day.

Like the French, the Brits were late to the game. They made their claims on Newfoundland in 1583 and the failed experiment at Roanoke was undertaken before the century was through. In 1607 Jamestown, their first successful New World colony, was founded and in 1608 the Brits established their first trading post in India. In 1609 they established a colony on Bermuda and from there they set out to lay claim to the east coast, North American interior, Caribbean and East Asia. Plymouth, Barbados, Guinea & Massachusetts were added to the Empire by 1630 and over the course of the rest of the decade they continued to add new colonies including Maryland, Virginia, Rhode Island and Connecticut. In this same decade, the British East India Company was founded and had a fort in Madras built by 1644. In 1655 they conquered Jamaica with the intention of turning it into a major slave market. In 1661 they erected a fort on the Gambia River and three years later they took New Netherlands from the Dutch, renaming it New York a few years later. For the rest of the century, Britain worked to protect their colonies from increasingly hostile native groups in North America while closely watching as the British East India Company took control of the sub-continent.

In the 1700’s Britain was forced to defend her colonies from European rivals. In 1732 they allowed the private colony of Georgia to serve as a buffer between the Spanish in Florida and French attempts to settle in the area. In 1751 they rebuffed a French attempt to establish themselves in India. From 1754 to 1763 they fought, and won, the Seven Years War which gave them control of France’s American possessions short of New Orleans (they’d get that soon enough). From 1769-70 Captain James Cook opened up New Zealand and Australia to colonization, spelling disaster for the local population (not that this wasn’t true elsewhere, but it seems to be largely ignored in the American education system-Google Tasmanian genocide). All of these victories and new discoveries were either undone or overshadowed by the American Revolution. This not only saw Britain lose her former colonies on the American east coast but provided the rest of her colonies with a blueprint for rebellion and independence. With a sizable chunk of North America lost, Britain turned its eyes on West Asia and Africa, making its first play for South Africa in 1795 and making Oman a protectorate in 1798.

The 1800’s saw two major trends for the British Empire; removal of indigenous peoples from their conquered colonies and the expansion of their territories in Africa and Asia. As for the first trend, it took place mostly in Australia, the Falklands and Tasmania. The most egregious example, as I mentioned earlier, was the expulsion of the Tasmanians from their homeland in 1831, though they did a similar removal in the Falklands, removing Argentinians from the islands in 1833. As for their efforts in Africa and Asia, Brits were flooding into South Africa in the 1820s, they invaded Afghanistan unsuccessfully from 1839-1842, fought the Sikhs in 1845 and put India under direct control of the crown in 1858. They annexed Lagos in 1867 in an effort to end the slave trade, after buying and selling slaves for generations mind you, and in 1868 annexed Lesotho as well. In 1874 they took Ghana and the Gold Coast, in 1876 they assumed joint control of Egypt, they launched a second unsuccessful war in Afghanistan in 1878 and subjugated the Zulu in 1879. They took full control of Egypt in 1882 and were major players in the scramble for Africa. Before we move on to that, I’ll add that this was also the time that Australia was populated by Brits due to a gold rush in the 1850s and was also the period where Canada expanded to the West Coast and became a single large colony.

I could try and list all of the various countries the British came to control in Africa, but it is a huge list and there are so many name changes between colonial names and modern names that I think it would bloat this article more than it already is. Just look at a map of colonial Africa and it will be clear that no region of the continent didn’t have some proximity to the British and their colonial system. From 1884 all the way to the post World War I protectorate period, the Brits were adding colonies to their Empire. Kenya, Uganda, Tibet, Rhodesia, Malawi, Benin, Iraq, Trans-Jordan, Palestine and the Sudan were all added to the empire as colonies or protectorates during this period. Also during this period all unrest in the colonies was met with overwhelming force. In 1897 they burned Benin City, in 1919 they fired on peaceful protesters in Amritsar and their history in their Middle East protectorates speaks for itself. After World War II, they met the same fate as the rest of the colonial powers. Protectorates regained the right to self-rule and colonies undertook independence movements that were resisted at first, but eventually became commonplace. 1907 saw New Zealand gain Independence and India followed in 1948. The Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya began in 1952 and the violence on both sides helped Britain come to terms with the end of their African empire. From 1956 to 1980 upwards of fifteen African nations declared independence from the British Empire, essentially ending the global power that had once been the British Empire.

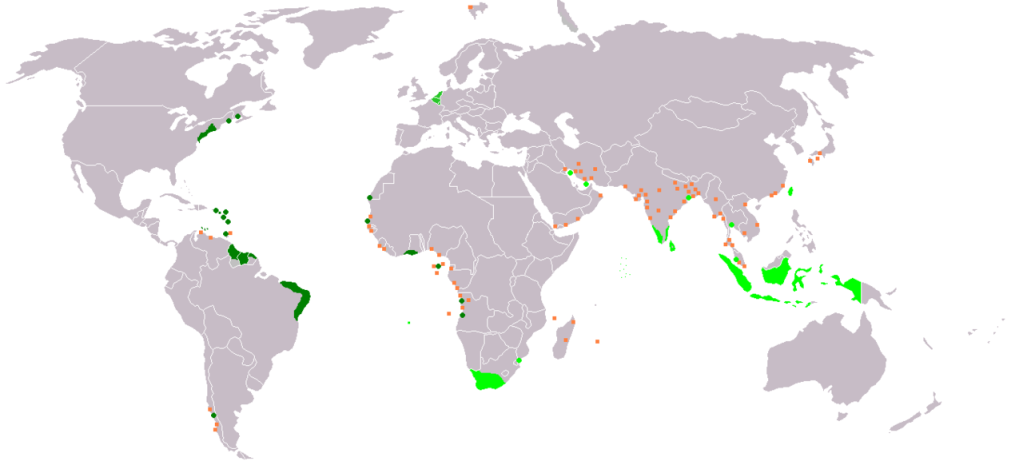

Even after all of the war, genocide and exploitation the British Empire was responsible for, it is still essentially an Empire today, albeit of a different sort. Fourteen of its territories still remain under British control and a slew of former colonies have been organized into a Commonwealth under the Queen. She does not have any real power in this Commonwealth as all members are sovereign nations, but it is still an odd remnant of the Colonial period in the modern day. Whereas many empires see their language and culture as their major ‘gifts’ to their colonies, the major British influence seems to have been her legal system, which is still used all over the world today despite the Brits themselves being largely out of the picture.

6. German

The next three entries are true latecomers to the colonization game, but they tried their damnedest to emulate their larger rivals and in many cases matched and even exceeded their brutality. As a nation, the Germany we know today did not exist until Bismarck unified the country between 1870-1880. It was Bismarck himself that set-off the scramble for Africa with his Berlin Conference and in the short time Germany was a colonial power, she did her best to gobble up as much land as she could. In 1884 Germany annexed Togo, Cameroon and Namibia under the guise of offering protection from the other European powers. In 1885 German warships showed up on the coast of Zanzibar and by the next year they had control Tanzania. In 1897 they added Rwanda and Burundi and in 1898 begin to amp up naval production to protect their fledgling empire and keep the Brits at bay.

Rebellions were common and the Germans were ruthless in their response. When an ethnic group in German Southwest Africa began targeting German colonists, the response was to drive 8,000 of them into the Kalahari desert where they died of exposure, starvation and thirst. Another uprising by the Maji Maji in 1905 was met with an orchestrated famine that killed thousands. At the same time, they tried to undermine their fellow colonial powers, pushing for Moroccan independence in 1905 much to the anger of Britain, France and Spain. Bismarck was eventually removed from the equation by the Kaiser and the Empire quickly fell apart. World War I saw the Germans fighting a two-front war in Europe and also an all-out war in Africa where their colonies were suddenly up for grabs. The Germans in Africa surrendered in 1918, after thousands if not millions of Africans were killed, and the German Empire was divided up by the victors. Most of their colonies went to the British, though the French took partial control of Cameroon and Togoland alongside them. The only oddballs were Rwanda and Burundi, which went to Belgium.

Unlike the rest of our list, the Germans passed very little on to their colonies in the form of culture or government. Instead the German colonies were largely a failure in every respect. They made the home country no money, in fact they were financial drains, and less than 20,000 colonists are thought to have left the motherland for German possessions abroad. Perhaps the most sickening thing about the entire episode was that this seems to be where the Germans perfected their system of concentration camps and there are signs that the later medical horrors enacted by the Nazis got their start in Africa as well. Certainly something not enough people know about.

7. Japanese

As the only non-European nation on our list, Japan is obviously a special case. A largely isolated nation until the ‘opening of Japan’ by Matthew Perry in 1854, this event not only forced them onto the world stage but also showed them how vulnerable they were to Western military might. In the 1860s Japan began a major industrialization effort that changed not only the Japanese military, but its society into a more Western model. In the 1870s and 1880s the Japanese Imperial forces regained control of the home and surrounding islands before setting their sights on the mainland. From 1894-95 they fought their first modern war with China, taking Taiwan as a prize. After years of unequal treaties and near invasions, Korea was made a protectorate and then finally annexed in 1910. Then came a confrontation with the Russians that shocked the world. In the Russo-Japanese War of 1904, Japan sent Russia packing and proved that Europe did not stand alone as global military powers. This also led to the lease of Manchuria passing from Russia to Japan in 1905, giving the Japanese a long sought after position in mainland China. After WWI they took the Germans possessions in the Pacific, beginning their conquest of the Pacific islands. They tried to take advantage of the Russian Revolution as well, but their inroads further into China did not last after 1925. In 1931 the false-flag ‘Manchurian Incident’ was used as a pretext to invade China, which they did, separating Manchuria from China and installing a Japanese controlled puppet-emperor. This puppet helped the Japanese feign legitimacy in the region, but violent suppression was still required to subdue the conquered Chinese.

The legacy of Japanese occupation in Manchuria and Korea is complicated. In addition to ruling viciously when their control was questioned or threatened, the Japanese set up a modern infrastructure that catapulted both regions into the modern era. In Korea specifically, the Japanese also seemed to have invested heavily in education and cultural assimilation efforts. Like most colonial improvements, these were not intended to simply uplift the conquered population. The Japanese gave much of the best Chinese farmland in Manchuria to Japanese colonists from the home islands. The Japanese hoped to solidify their hold on these two colonies and use them as bases from which they could invade the rest of the region, but their efforts ended with their loss during World War II. While they made minor Pacific gains early in the war, their ultimate defeat costed them not just millions of Japanese lives, but their overseas imperial ambitions. From 1946-1948 the allies, including US troops, oversaw the relocation of Japanese colonists to their homeland, thus forcefully ending their colonial occupation. While the Japanese may not be a true colonial empire by some standards, they tried to be and for that I figured they ought to be included on this list.

8. Belgian

Our final entry will be kept brief, though it is a harrowing story everyone should be at least somewhat familiar with. The history of Belgian colonialism is especially short, exceptionally violent and easily one of the darkest chapters of colonial history, which is saying something. King Leopold II of Belgium was late to the colonialism effort and was not happy about this fact. He dreamed of acquiring a ‘model colony’ for Belgium that would bring in revenues for the crown and raise Belgium’s prestige in Europe. Using private money from European backers, Leo founded the Congo Free State under his direct control (it is his personal property not a Belgian colony). His goal was to use the local population as slave labor to harvest ivory and rubber from the region. Obviously the locals weren’t too keen on the idea and Leopold had his men resort to horrific levels of barbarity to induce labor or punish non-compliers. The tactic that earned him the most international infamy was the systemic use of maiming. Pictures began to flood the international news outlets of Congolese men, women and children with missing hands or arms. On top of this, the Belgians brought along a host of diseases that killed over a million Africans. By 1908 pressure had mounted on Leopold to end this reign of terror and so he made the Free State an official colony.

Money was then poured into the Congo to turn it into the ‘Model Colony’ Leopold II had dreamed of. Areas became high specialized, infrastructure sprang up in the dense jungles and it looked like the worst days of colonial rule were behind them. Yet this slightly improved society was still highly segregated, with whites controlling jobs and using Belgian troops as strike breakers when their mistreatment caused workers to rebel. During WWI the Belgians and Congolese fought the Germans and took Rwanda and Burundi for the Belgian crown, in the process propping up the Tutsi upper-class minority (this would play a major role in the later Rwandan Genocide). In World War II they battled the Italians on the side of allies and in the subsequent decade began an urbanization effort that aimed to create a European style middle class in the Congo. By 1960 though, the Congo had managed to add its name to the growing African Independence movement, keeping Belgium as a sort of unofficial advisor/protector for a short time afterwards. While the Congo certainly gained something in the way of infrastructure and urban development, the cost was decades of senseless brutality at the hands of those who meant to use their country as a financial asset. Hardly a trade anyone in their right mind would make, given the option, which of course, the Congolese people were not.

Whew this was a long one. I hope you stuck with it and learned something. If you found this article interesting check out 10 Brutal Sieges Pt. 1 (Before 1500), 10 Brutal Sieges Pt. 2 (After 1500), 5 Famous Last Stands, 9 UNESCO World Heritage Sites: West Asia & North Africa Edition or visit our Archives.